crisis

Crisis Leadership: What Your Organization Needs To Know

April 2023

crisis

Crisis Leadership: What Your Organization Needs To Know

April 2023

Crisis is often associated with a sudden, external shock. Some of us feel out of control, some of us want to take more control. It’s easy to blame some great external force when we are humbled by events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Yet catastrophe typically shows us the consequences of accumulating issues that have been ignored and suppressed over time.

In this sense, crisis is our greatest teacher. A painful teacher, yes, but one that arrives to check our work and reveal our mistakes. To uncover human negligence. The cost of these lessons is high – too high – particularly when we realize they are of our own making. While macabre and morally repugnant, within each crisis is the long overdue message of change. An opportunity to remake a better system that truly serves us. By judging the event rather than the decisions that created it, we never learn the lesson and repeat the cycle again.

The 2023 Turkish-Syrian earthquake which killed over 50,000 people and displaced 1.5 million people is widely blamed on failure to enforce building regulations. The 2020 Beirut explosion which led to the collapse of the Lebanese government was preceded by years of warnings. Similar stories can be found in the tragic train derailments in Greece and the United States due to ignored problems.

Again and again, we compromise on making necessary change and inevitably jeopardize our survival. And in this moment of crisis – unexpected and abrupt – people react differently, even unpredictably, relative to non-crisis time. Leaders need to learn how to regulate the instinctive fight/flight reasoning that emerges during these short and powerful events.

To maximize adaptation before, during and after a crisis, leaders and organizations must know:

By riding the wave of disruptive change, businesses, government agencies, and non-profits not only strengthen their ability to survive but even emerge better suited to the new world order.

Crises are events that are perceived by leaders and organizations as unexpected, highly impactful, and potentially disruptive to the status quo. Their low predictability makes them difficult to prepare for, rendering past experience inapplicable to the situation at hand. Simultaneously, they carry high and often negatively perceived consequences for individuals, organizations, and society at large.

Take the war in Ukraine: member nations of the European Union were caught unprepared to forego Russian energy supplies. Germany chose to reactive its coal power plants only to find that low water levels in the Rhine River made it difficult to transport coal effectively. 57% of France’s nuclear generation capacity was offline for overdue maintenance. Surprised by the sudden change in supply needed to heat homes during winter, the European Union faced an energy crisis.

Crisis occurs when discreet events create a “tipping point” that expose the accumulation of flaws in a system. Many times, organizations impulsively react to withstand the shock and restore the old equilibrium. This approach misses the opportunity to learn, adapt and prepare for the next environmental change. Focusing just on discreet crisis events prevents leaders from taking responsibility for and resolving the situation.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans in the United States, resulting in 1,392 fatalities and causing close to $150B in damages. While the storm caused catastrophic damage, its staggering impact was more so the result of a degenerating system. Simply blaming the crisis event would lead to no deeper insights. Instead, investigations found that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was responsible for the failure of the flood-control systems. Mismanagement and lack of communication between local, state and federal agencies further led to deaths from thirst, exhaustion and violence. The hurricane exposed compounding, man-made failures from which we can learn and improve upon.

The process of accumulating flaws – a crisis-in-the-making – follows a series of common patterns. Typically, a leader or organization:

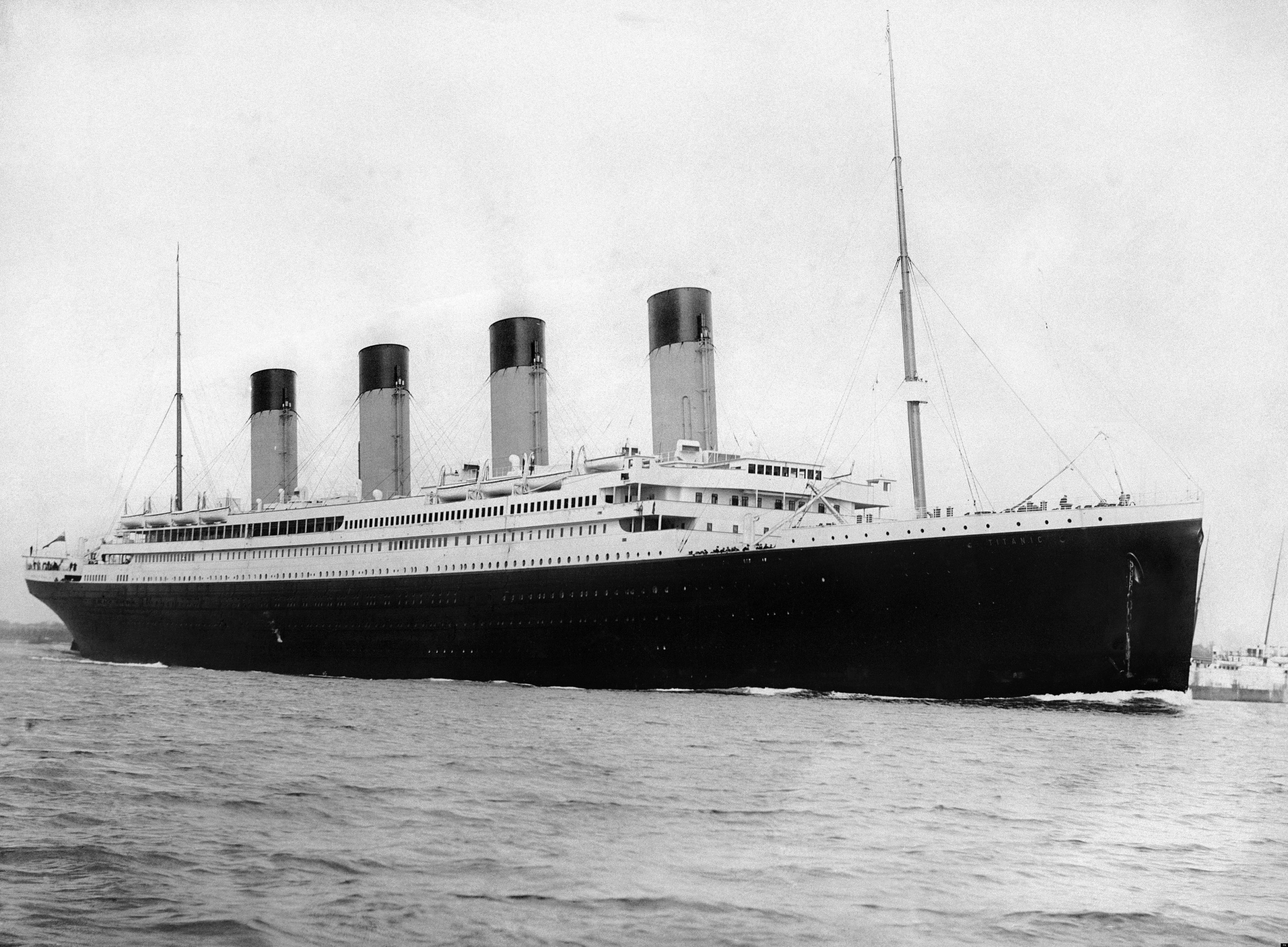

These patterns are perhaps best exemplified by the RMS Titanic Captain, Edward Smith, who ignored warnings of ice, declaring, “[he] could not imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.”

As a leader, preventing an existential crisis necessitates:

In 1997 Netflix introduced DVD mail-order to upend retail chains such as Blockbuster. Early on, Ted Sarandos and Reed Hastings of Netflix were keen to take advantage of the burgeoning internet to distribute movies. They originally conceived of a “Netflix box” where customers could download movies overnight and watch them the next day. By the mid-2000s data speeds reached a point where this vision could become a reality.

Vice President of Content Robert Kyncl was asked to volunteer on the Netflix box project. He later wrote:

“Now, volunteering to lead a new initiative is a very stupid thing to do at Netflix. The company’s culture prides itself on relentless focus, dispassionately eliminating business initiatives that are not core to the overall strategy.”

Despite this professional risk, Robert persisted in building the new box service. In 2005, the new box was ready to launch.

And then Robert stumbled across a new website called YouTube.

“Witnessing the popularity of YouTube was a revelation. And it caused us to stop our launch and pivot to a service that would allow consumers to stream movies remotely instead of downloading them. That pivot took two long years, during which we had to renegotiate all our rights and build an entirely new architecture to host and serve content. We had to transform our “Netflix box” from a hard drive that would download video to one that would stream it.”

Netflix, upon realizing the winds had changed, adapted its entire approach to mimic YouTube. Weeks before launching its streaming service it spun off the Netflix box into a company called Roku. Today, Netflix accounts for 40% of total internet traffic in North America and 15% of total global internet traffic. The scale of Netflix’s internet traffic has forced service providers to quietly recreate the entire infrastructure of the world wide web.

Many credit Netflix with its disruptive DVD mail-order business model. However, what differentiates Netflix is its organizational adaption. They are unafraid to reduce organizational complexity, remain attuned to environmental changes, and look to the future to take big bets without fear. They quickly adopted an entirely new business model and left their old one behind.

These principles of change separate the Blockbuster’s – bankrupt and forgotten – and the Netflix’s – the change makers that come to define the landscape.

When problems are ignored, become bigger and eventually go public, they are considered organizational crises. Some common organizational crises include:

During crisis, an organization must match the pace of change until it reaches a new equilibrium point. This new equilibrium point will present a new homeostasis – quite different than the previous way of operating.

Based on 3Peak Coaching & Solutions’ experience with clients, to emerge from chaos crisis leadership must:

Emotional contagion occurs when one person’s emotions and behavior lead to a replication of emotion and behavior in others. Emotions like fear can spread like a virus from person to person. In this exchange, decision making is hampered and “herd mentality” leads groups to make illogical decisions.

On September 11, 2001, a coordinated terrorist attack was carried out against the United States. Amongst the shock, grief and outrage of these attacks, the United States would eventually launch two ineffective wars in the Middle East, pass a slate of invasive surveillance legislation, and expand the powers of the government. Reacting from emotion, the United States made a series of policy decisions that severely strained its domestic and international stability.

Scientist and policy analyst Vaclav Smil writes:

“Public reaction to risks is guided more by a dread of what is unfamiliar, unknown, or poorly understood than by any comparative appraisal of actual consequences. When these strong emotional reactions are involved, people focus excessively on the possibility of a dreaded outcome rather than trying to keep in mind the probability of such an outcome taking place.”

This focus on dreaded outcomes prevents us from making the right decisions and distort the lessons we can learn after the event. Expanded to a group setting, unregulated emotionality in a collective leads to irrational behavior and can even create future crises.

Amidst crisis, the first step a leader must take is to contain the emotional contagion in their organization. Awareness of emotional contagion is important for managing our own emotions and behavior in order to then assure the wellbeing of others. Remember, on a plane we put on our own oxygen mask first.

The virality of emotions like fear keep systems locked in fight/flight/freeze and handicap efforts to move forward. While each individual must be free to feel and process their unique emotions, efforts must be put into place to disrupt heightened emotions from spreading between individuals and groups.

“Houston, we’ve had a problem.” So began a harrowing message to NASA following an explosion during the Apollo 13 space mission. Confusion and chaos broke out between the astronauts and mission control. Astronaut Fred Haise recalled, "We had seven caution and warning lights on. Generally, there was never a failure in one system that would go across so many different systems."

Mission control was equally confused, unable to make sense of several unusual readings. This led one controller to famously say, “We may have had an instrumentation problem.” It wasn’t until astronaut Jim Lovell realized a look out the window would provide more information than the instruments that he noticed a gas of some sort venting into space.

When a crisis event hits, one of the most important functions a leader can perform is to help make sense of events. When tried and true “instruments” fail, a leader must step back to look at the entire situation. This requires maintaining emotional calm amidst chaos. Next, they must make a commitment and move to action, even if the action is wrong. And once in a commitment, they must not remain blinded to alternative strategies.

In the case of the Apollo 13 mission, the commitment to shut down all power and save its batter power enabled the crew the eventually return back to Earth. Additionally, this gave NASA time to brainstorm 5 strategies to save the astronauts. Throughout this entire period, clear communication, information gathering and sense making kept the astronauts alive.

Further, in sense making leaders can choose to either frame crisis as bad and terrifying or as manageable and filled with opportunity. The ability to frame crisis in an empowering way enables more rational, prudent, and ethical decision making.

Consider how the astronauts frame their experience:

In crisis, get clear on the facts, set a positive frame, commit to action and be carefully to adapt to new strategies as new information becomes available.

In 458 BC, the Aequi tribe attacked the Roman city of Tusculum used by the wealthy and elite for leisure. The republic’s senators fell into a panic and authorized the nomination of a dictator. The senators approached Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a retired military leader turned farmer. Cincinnatus defeated the Aequi, disbanded his army and returned to his farm, abandoning total control 15 days after it had been granted to him.

When a popular uprising caused a crisis in 439 BC, Cincinnatus again left the farm to restore order to the republic. He established himself as king over Rome, quelling the rebellion within 21 days. Again, he resigned his commission and returned to farming. Again, democracy was reestablished.

Beyond his humility and prudence in the face of total power, Cincinnatus also role models the utility of concentrating power to make quick decisions. In times of crisis, consensus-based decision making takes too long to respond to the changing environment. Instead, democratic decision making must yield to more authoritarian styles of decision making.

In the face of ambiguity, any decision is better than paralysis. With each movement forward, feedback gained from the environment will help leaders adjust and adapt to the new normal. While gathering diverse, expert opinions are important, leaders need to move fast and make decisions autonomously. Paradoxically, this does not mean the leader-in-charge takes on more control: with greater complexity comes the greater need to empower teams to also make quick, autonomous decisions. At every level of the hierarchy, the priority is to take action, gain feedback, adjust the course of action.

And like Cincinnatus, when the acute crisis event has been navigated, leaders need to relax their style to allow for democratic and consensus decision making to return. Fluctuating between different decision making processes and different speeds is vital during change.

Eric Blair walked over to the bulkhead of the molasses tank and leaned back on its warm side. For the first time in 3 years, he didn’t meet his wife for lunch, preferring to enjoy eating alone. At 12:30 PM, "a thunderclap-like bang! and a sound like a machine gun” roared across the area. The molasses tank exploded sending 2.3 million U.S. gallons (8,700 cubic meters) weighing 12,000 metric tons hurtling through the streets of Boston at 35 miles per hour (56 kilometers per hour).

The sugar tsunami reached a height of 15 feet as it engulfed and suffocated men, women, children, and horses. Buildings collapsed or were ripped from their foundations as the wave of molasses hurtled through northern Boston. A Boston Post reporter wrote, “Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was.” All told, 21 people died and 150 were injured in the Great Molasses Flood of 1919.

Every available ambulance, policeman and fire truck was sent to the area. The commander of the USS Nantucket sent 100 cadets to aid the rescue. Hundreds of volunteers showed up to save people and begin the clean-up efforts. For weeks farmers carted off molasses to neighboring towns.

When hundreds or thousands of people show up to help, disorganization can lead to further chaos. In times of crisis, leaders must emphasize and re-emphasize clear roles, crisp communication, and build trust.

To facilitate this, leaders must become the “hub” of coordination. By creating direction and alignment, resources and people will be properly coordinated. Clear roles and responsibilities is paramount and is the single most important factor in creating “swift trust” amongst teams that have never worked together before. Where “boundarylessness” emerges, conflict and dysfunction will follow. Boundarylessness also encourages emotional contagion to spread.

Once in role, leaders need to create open, honest communication channels. Honesty allows for negative feedback and fosters trust. Communication is the glue that allows leaders to get all the information, disseminate decisive decisions, and foster collaboration. Set direction publicly and visibly while remaining encouraging yet realistic.

Crisis has the power to entirely transform our social systems. Between 1346 and 1353, the Bubonic Plague ravaged Europe killing 30 – 60% of its population. Until that time, society had been organized through a social system called feudalism. The king owned all the land, which was parceled to the nobles and was worked by the peasantry. With no social mobility, the peasantry toiled from birth to death.

During the plague, the vast mortality upheaved the entire social structure. With a reduction in labor supply, the peasantry demanded higher wages. The richest 10% of society was forced to distribute 20% of overall wealth to the lower classes. Medical institutions questioned their competency, institutional religion was heavily questioned, and the persecutions of Jews began. Women significantly expanded their right to own land, start a business, and choose their own mate.

With increased wealth equality and social mobility, feudalism was dead.

The decisions made in crisis create the system we inherit after a new equilibrium has been established. While crisis naturally draws us to short-term thinking, leaders cannot lose sight of their values during large-scale change. A leader must be able to hold both the short-term needs to survive with the long-term creation of a new system.

Crisis offers choice points, during which we can move to:

In the case of the Bubonic Plague, pragmatism won over ideology, allowing women some semblance of autonomy and agency. Through the lens of our modern values, we can applaud this increase in egalitarianism and human rights. Conversely, the choice to demonize the Jews and Romani as the cause of the plague led to severe persecutions, extermination and mass migration events. A pattern that would ripple through the fabric of European history for hundreds of years.

Creating social systems that move us closer or further from our values are woven into each decision during crisis. Which will you choose?

“Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes fire. Likewise with randomness, uncertainty, chaos: you want to use them, not hide from them. You want to be the fire and wish for the wind.”

- Nassim Taleb

Once a crisis event has concluded, an organization that seeks to learn from the experience will naturally ask itself: what’s next?

The urge to return to ways of working exemplified by the previous equilibrium will be strong. Yet, once pandora’s box is opened, it cannot be closed again. Companies that allowed fully remote work during COVID-19 are struggling to convince and retain workers that they must return to the office full-time. The decisions we make during crisis matter.

Beyond accepting the “new normal”, organizations can prepare for the next shock event by learning the right lessons, practicing in simulations, and building the skills of adaptation.

Crises present wicked learning environments – where information is hidden and feedback is delayed or inaccurate. In such environments, we often “learn” the wrong lessons. As such, what we learn during crisis may not be as important as what we intentionally choose to learn after crisis. After the crisis event has subsided, leaders will benefit from casting a wide net, soliciting feedback from many, diverse perspectives. The emphasis is not to cast blame or explain things away; instead, look to earnestly improve.

Research highlights 5 key areas to investigate after crisis:

After the right lessons have been learned, leaders can implement best practices to prevent and practice for crisis.

Don’t underestimate small changes that carry disproportionate impact. Looking for sexy changes misses the point. For instance, the easiest ways to massively cut human mortality rates include:

In combination, these actions reduce more deaths than those experienced from terrorist attacks.

Whether preparing for fire, acclimate weather, or earthquakes, drills are an effective mechanism to support people through emergency.

Darwin’s “survival of the fittest” has been twisted and has come to be associated by the collective as “survival of the strongest”. Yet natural selection does not always reward the strongest. Fitness is measured in terms of adaptation – the ability to flourish in a changing environment.

After stability has been restored, leaders have the choice to create a culture of adaptation within their organization. Based on 3Peak Coaching & Solutions’ research and experience, there are 3 critical areas to develop to create an adaptive culture:

In combination, these 3 areas give organizations the best possibility to flourish and thrive in moments of adversity.

Crisis events are sudden, unpredictable and carry high consequences. They usually are manifestations of a series of missteps that have been ignored. In a crisis, a leader can simply try to withstand the shock, can double down on their strategy, use crisis as an opportunity to enact positive change, or end in catastrophe.

To prevent the accumulation of ignored problems, a leader will benefit from choosing facts over stories, reduce complexity, attune their senses to the ever-changing environment, and learn to process their emotions.

During crisis, a leader must support others to manage the emotional fallout, constructively make sense of the situation, concentrate power for the sake of decisiveness, clarify roles, expand honest communication, and keep an eye on the future system that is being authored with each decision.

After a crisis, a leader can take full responsibility by learning the right lessons from their experience, promote practicing for emergency situations, and develop organizational adaptation. Organizational adaptation is achieved through leadership development, individual wellness, and change effectiveness.

Reading about crisis and implementing its lessons are not the same.

Looking for support? Tell us about your team!